By Stephen Dillon

As uprisings against racist state violence swept the United States in the summer of 2020, a question circulated on the evening news and across social media: Why would people destroy their neighborhoods? Why would they destroy their own homes? I want to offer one of many answers to this question by turning to that iconic time of antiracist struggle, the 1960s.

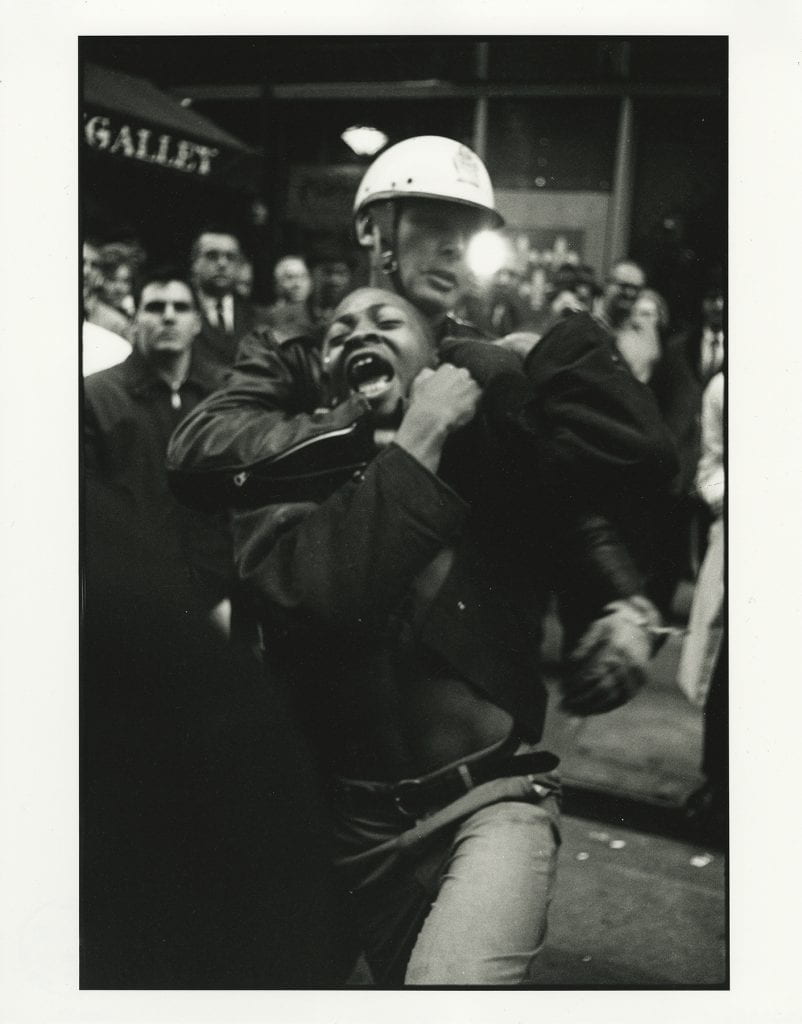

Throughout the early 1960s, the photographer Danny Lyon took some of the most circulated photographs of the civil rights movement. Perhaps his most well-known is of the seventeen-year-old honor roll student Taylor Washington’s eighth arrest. In the grainy, blurry black-and-white photo, Washington is choked by a police officer and yells in defiance as he is dragged away. This particular photo documents the dehumanization and resilience at the heart of the movement for Black freedom as well as in Lyon’s lifelong photographic practice.

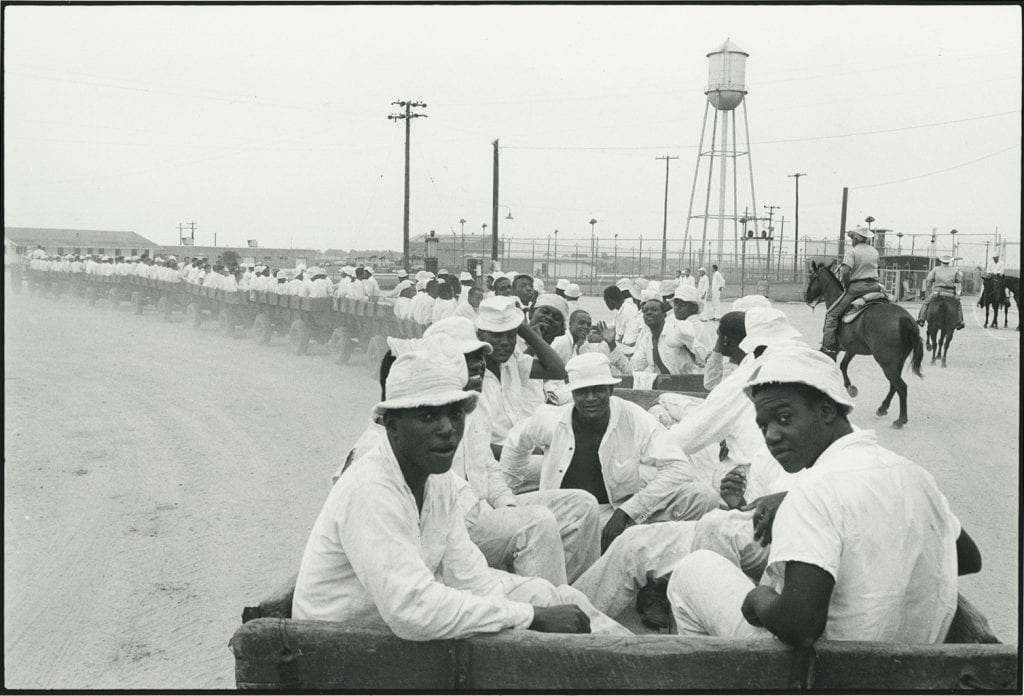

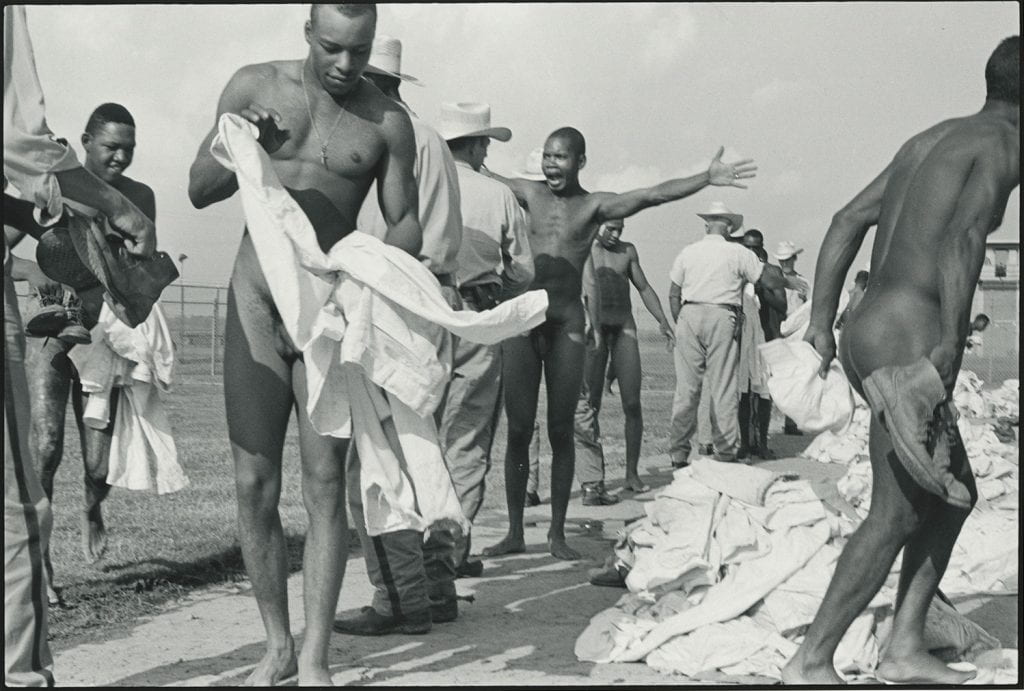

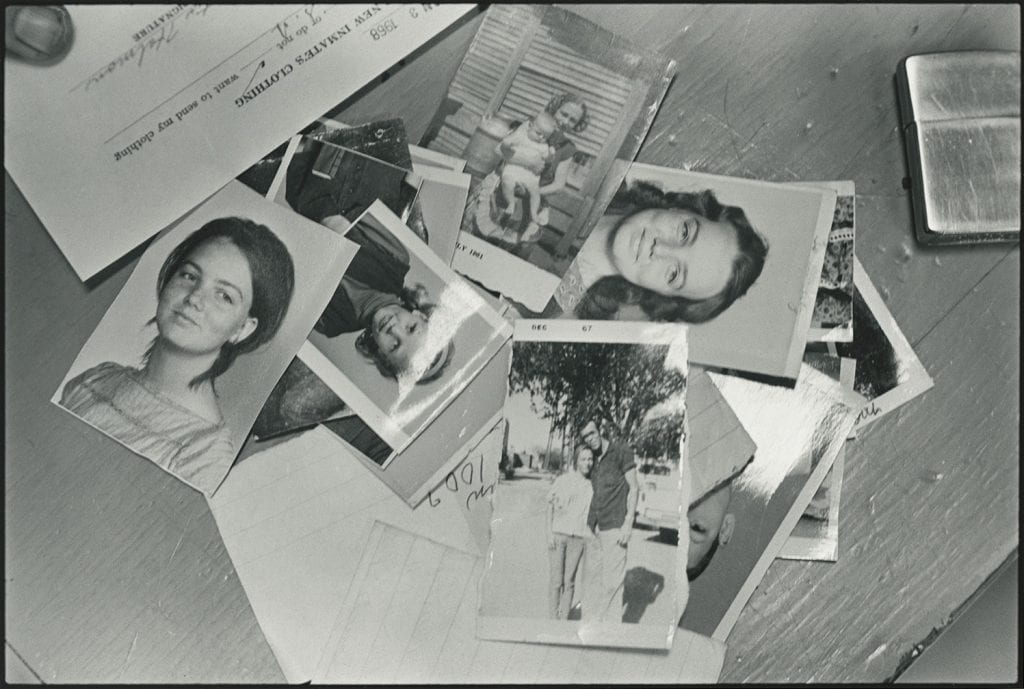

While many of his photographs would become iconic depictions of the nonviolent unrest of the early 1960s, in the late 1960s he began photographing prisons and imprisoned people. The shift in his subject matter accompanied a larger political shift away from rights and toward the physical institutions central to white supremacy. The prison became a central site of struggle for the many radical movements of the late 1960s—as Native, Black, Chicano, and radical white activists were imprisoned for their activism and imprisoned people became radicalized by the revolutionary movements from Oakland to France to Cuba. The prison was seen by post-civil rights activists as a central nexus between imperialism, racism, and freedom.

In this selection of Lyon’s photographs we see the bodily and affective violence of the prison state—the routine sexual assault of imprisoned people through strip searches and cavity searches; the afterlife of slavery in the labor imprisoned people perform codified by the Thirteenth Amendment; and the destruction of imprisoned people’s communal and affective ties with the outside world by taking their possessions and putting them in cages. These are world-destroying processes that leave in their wake domination, abuse, illness, isolation, and premature death. And as we know so well now, incarceration was a way to attack Black communities, cultures, knowledges, and the very ability to make a home. What is home if a no-knock warrant allows police to shoot you while you sleep? What is the meaning of home if men in blue-collared shirts take you in broad daylight and put you in a cage for decades? What is home if you are shot walking home from the grocery store? Lyon’s photos are just one small reminder that home has no meaning if there are no structures to support its existence. And so looting a Target, or destroying a bank, or burning a police station are not self-destructive acts, rather they are a powerful declaration that home is uninhabitable. They are a statement that home requires more than predatory loans and low-wage service labor. They are a roaring critique of things as they are, and they ask for a new order of the world to take shape out of the rubble. Simply, home is not home for far too many people.

You must be logged in to post a comment.