By ASHLIE SANDOVAL

Out of 19,000 items at the Mead, Amherst College’s on-campus art museum, sixty items were labeled in the online database with the words “African American” in the keywords, description, or label text (as of this writing). Those items were created by thirty-two artists, out of which twelve self-identify as Black. Thirty-one items were added in the last five years. This picture is a collection of the Mead’s images for each of these items (six items had no image).

The following was revealed in investigating how other American communities of color are framed in the Mead’s collection:

The word “Latinx” produced no results. The word “Latino” produced six results, five pictures of Abraham Lincoln and one etching of a Spaniard. The word “Hispanic” produced seventeen results, three of which were photographs of people, fourteen of which were objects of pottery.

The words “Asian American” produced eleven results. Three results were also listed under African American (two) and Hispanic (one). Two results were made by Asian artists, neither of whom are identified as American. “Korean American” produced no results. “Japanese American” produced no results. “Vietnamese American” produced no results. Japanese American (without quotations) produced thirty-one results, none of which were objects created by Japanese American artists.

While the Mead may carry many more art pieces by artists of color than these searches portray, these search results speak to what Ruha Benjamin has called “default discrimination,” a type of discrimination that happens when institutions do not attend to the historical and social contexts of their work.

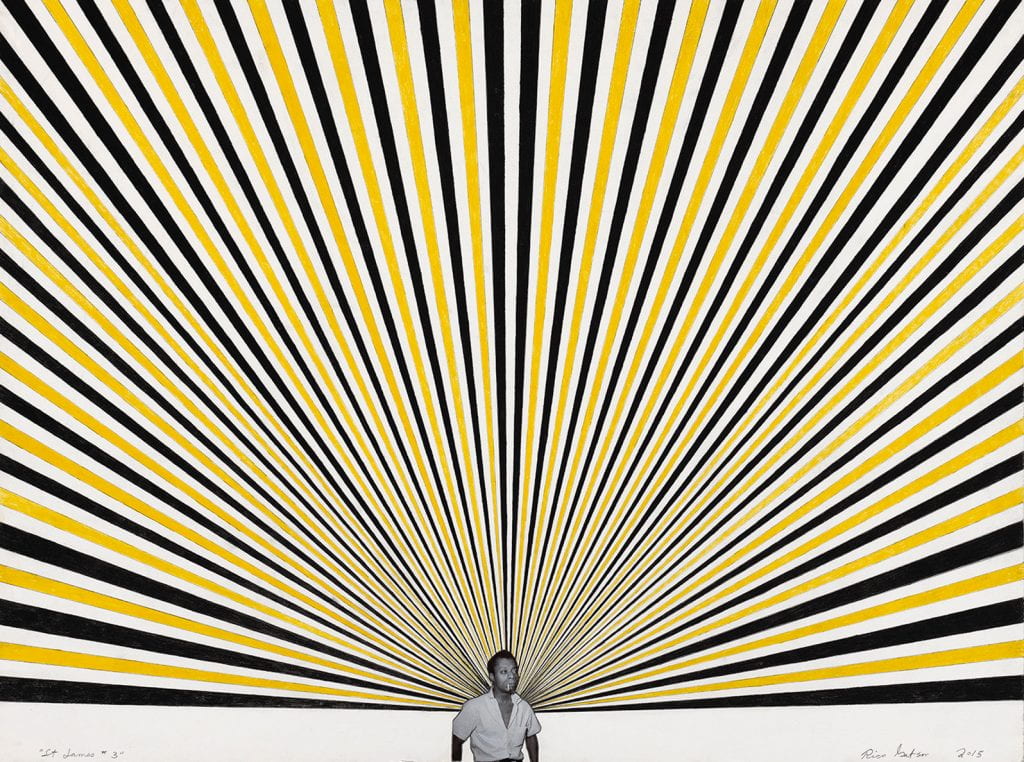

Considering how visual culture has been thoroughly shaped by both white ways of seeing, cataloguing, and framing as well as white ways of not-seeing, the question becomes for some artists and scholars: How do we address visuality itself? As art historian Huey Copeland points out, for Black people “visuality . . . —thanks to its frequent denigration of the black image and its despotic manifestation in the white look” has often felt like a medium that could not register “a whole body of blackness.” (1) In response to this condition, Black artists have used a range of techniques. Some artists have taken imagery out of their artwork, resorting to words to discuss race, such as Glenn Ligon.(2) Others imagine Black futures from within the mundane, such as curator Meg Onli,(3) and still others position iconic Black imagery into Black grammars of seeing, such as Rico Gatson with his collage portrait of James Baldwin, titled St. James #3 (above), part of his series “Icons” (2007–ongoing), which pays homage to Black artists, politicians, activists, and athletes, portraying them as saints.

As you look at these collected pictures of “Out of 19,000,” think of them as an exhibition within an exhibition. Questions to ask yourself as you view the pictures are: What are the time periods of the image(s)? What types of figures are portrayed (e.g., men, nudes, caricatures, symbols)? What emotions do you feel when looking at these objects? Who made the artworks? Who were the artworks made for? What becomes visible when we look at all of these images in these contexts? When we look at how Black images, bodies, and life are (not) represented, what can we say about how Blackness is portrayed?

Questions to take with you: How might you use visual culture to challenge white ways of seeing and not seeing? In looking at art, how might you reroute the course of visuality from subject matter to viewer, to collector, to institution?

“The Ancient Present Tense”

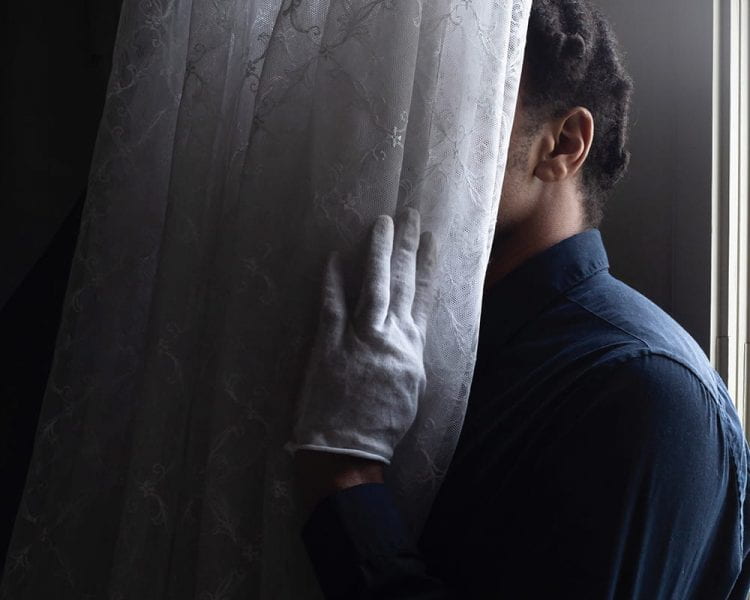

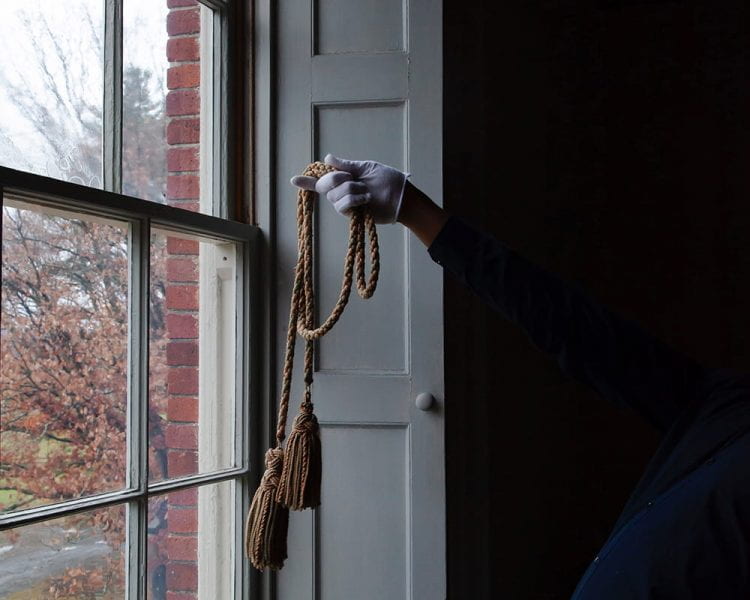

Jonathan Mark Jackson’s artwork (featured above) was inspired by Robert Roberts’ book titled The House Servant’s Directory,(4) the first book written by a Black man that was commercially published in the U.S. for two younger men entering domestic service. The book contains advice in essays such as “The Benefits of Rising Early” and “Hints to House Servants on Their Dress” and includes a series of recipes that span “Italian varnish” to “raspberry vinegar.” Returning to the last place Roberts served, Gore Place*, now a historical landmark, Jackson, a recent Amherst College graduate and fifth-great-grandson of Roberts, made a series of contemplative self-portraits throughout the house.

Jackson notes that the white gloves he wears in the pictures evoke the gloves worn by curators, archivists, magicians, or butlers.(5) Within the photographs, Jackson’s gestures seem to be both of the time period of Roberts and outside it, oscillating from pondering stances that Roberts might have held himself to whimsical, playful, and haunting gestures. Whimsy appears in photographs highlighting objects that some might deem as banal: a worn hook lock upheld by a white gloved forefinger and thumb for contemplation. The photographs mark history not only in the spectacular but in the mundane. The playful and haunting intertwine in a photograph titled Attic, a photograph of a white wall and square window, the inside of the window frame pitch black. Within the frame, we see Jackson’s white-gloved hands either holding the windowpane in place or attempting to communicate with someone beyond it. The hands almost appear enchanted or spectral, as Jackson’s partial silhouette is barely visible behind them.

Jackson notes that when he started this series, he briefly experimented with period clothing, taking cues from Roberts’s own description of what he wore. However, Jackson felt his “figure in the images became too trapped in a known stereotype or definition.” (6) His comment speaks to the boundaries, structures, and colonization of visuality. Perception is less an objective intake of the world than an apprehending of people and things according to relational and interpretative schemas. In seeing Jackson’s photographs, we make sense of them in reference to past images that we have witnessed, pinning down the meaning of the uniformed Black figure to prior renditions and positionings of this image. Removing himself from these associations, Jackson does not photograph himself in servant’s clothing nor in acts of service. Rather, in order to activate what Jackson calls “the ancient present tense,” an archiving and activation of multiple timelines at once, he dresses himself in modern-day clothing that can blend in with the home, his white gloves mediating between past and present.(7)

Jackson’s work evokes how Amherst College art professor Sonya Clark discusses her work centering the Confederate truce flag, a white dishcloth with three red lines woven into it, a flag mostly unknown despite its role in ending the Civil War. Clark says her work has the ability to be both a mirror and a sponge, a mirror reflecting the viewer back to themselves in some way and a sponge in that the piece can absorb all of the interpretations of it.(8) Jackson’s images reflect back the structure of our visuality, the multiple ways Black figures have become (un)familiar texts through time, as well as absorb the different stories of these periods—the different interpretations, experiences of, and desires for, the ancient present tense, each an example of our engagement with the work. What might these different stories tell us about how these histories compose our present selves?

As you view these images, what timelines, associations, and stories do they evoke for you? What is ancient for you in the photographs? What is present tense? Imagine looking at these pieces twenty years in the future. How do you think your associations and interpretations will change through time? What, do you imagine, will remain the same despite the passing of time?

Notes

- Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

- Glenn Ligon, “Neons,” GLENN LIGON, accessed November 2, 2020, www.glennligonstudio.com/neons.

- Huey Copeland, “About Time: Meg Onli in Conversation with Huey Copeland,” Artforum International, May 2019, Gale Literature Resource Center.

- Robert Roberts, The House Servant’s Directory: An African American Butler’s 1827 Guide (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006).

- Rafael Soldi, “Q&A: Jonathan Mark Jackson,” Strange Fire, March 14, 2019, www.strangefirecollective.com/qa-jonathan-mark-jackson.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Scott Turri, “Interrogating the Past: Sonya Clark Interviewed by Scott Turri – BOMB Magazine,” Bomb, July 4, 2019, bombmagazine.org/articles/interrogating-the-past-sonya-clark-interviewed.

* Please note: in the reading of the text in the audio clip above, “Gore Place” is mistakenly referred to as “Gore House.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.