by Ashley Elizabeth Smith

Indigenous Homelands

In her poem “Trees,” French-Abenaki artist and poet Cheryl Savageau remembers how her father taught her to see the world around her—look past the buildings, the cars, the pavement, in order to see the pond, the trees, the land.(1) For her, as for other Indigenous peoples, she says, the land is always first and everlasting. Everything else is temporary.

Listen to “Trees” and a short conversation with Savageau:

From an Indigenous perspective, the land is homeland. The land is home but also a living relative. Land is also a relative and part of the broad networks of relationships that sustain the community through acts of gathering and reciprocity.(2) In Wabanaki homelands, more commonly known today as northern New England and eastern Canada, which is where my own family and ancestors (settler and Indigenous) are from, there are many Wabanaki stories about this relationship. In one such narrative, published by Joseph Nicolar from Penobscot Nation in 1893, the First Mother, also known as Corn Mother, Corn Woman, and First Woman, comes from the plant world and gives birth to the first humans.(3) She then returns to the plant world to become the Corn that will feed her children. This story tells both of Wabanaki peoples’ literal kinship with the land, and their obligations to remember this relationship and care for the land as for a relative so that it will continue to sustain them.

Watch this interview with Savageau as she describes the story and process behind Corn Woman.

While Indigenous peoples and their connections to their homelands endure through colonization and settlement and into the present and future, many familiar narratives claim or imply that they have not. Regardless of our own backgrounds, many of us have been trained to see European settlement as the norm or a signal of progress. We have heard stories that tell us Indigenous people have vanished, or live only on reservations, or are part of the past but not the present or future. These are stories that serve to convince us that Indigenous peoples are gone and have been replaced by European and American progress.

Take the home of Amherst College, for instance, in the Kwinitekw, or Connecticut River, Valley. At first glance, we might see settler towns and colleges and farmlands. But this, too, is Indigenous space. It is Nonotuck homeland, and currently the home of many Indigenous people. Do you see it as such? If not, how might you come to? Can you, like the father in Cheryl’s poem, see beyond the temporary settler mask on the landscape and see the Indigenous homelands that are, now and forever, still family?

Questions to consider: When you look at your own homeplace, what do you see? What do you know of the Indigenous peoples whose homelands these were and are? Why?

Maps as Stories

How do we come to know the lands where we live?

One of the ways that we have been trained to know and understand land and space is with maps. What kind of storytelling does a map do? What stories and expectations shape our gaze? How might the same map offer different stories to different viewers? How might we come to approach the map in new ways, ask different questions of it, and see it in a different light?

More than a mere representation of space, maps like this one are socially constructed. They tell stories and make claims about space, which they inscribe onto our sense of understanding.

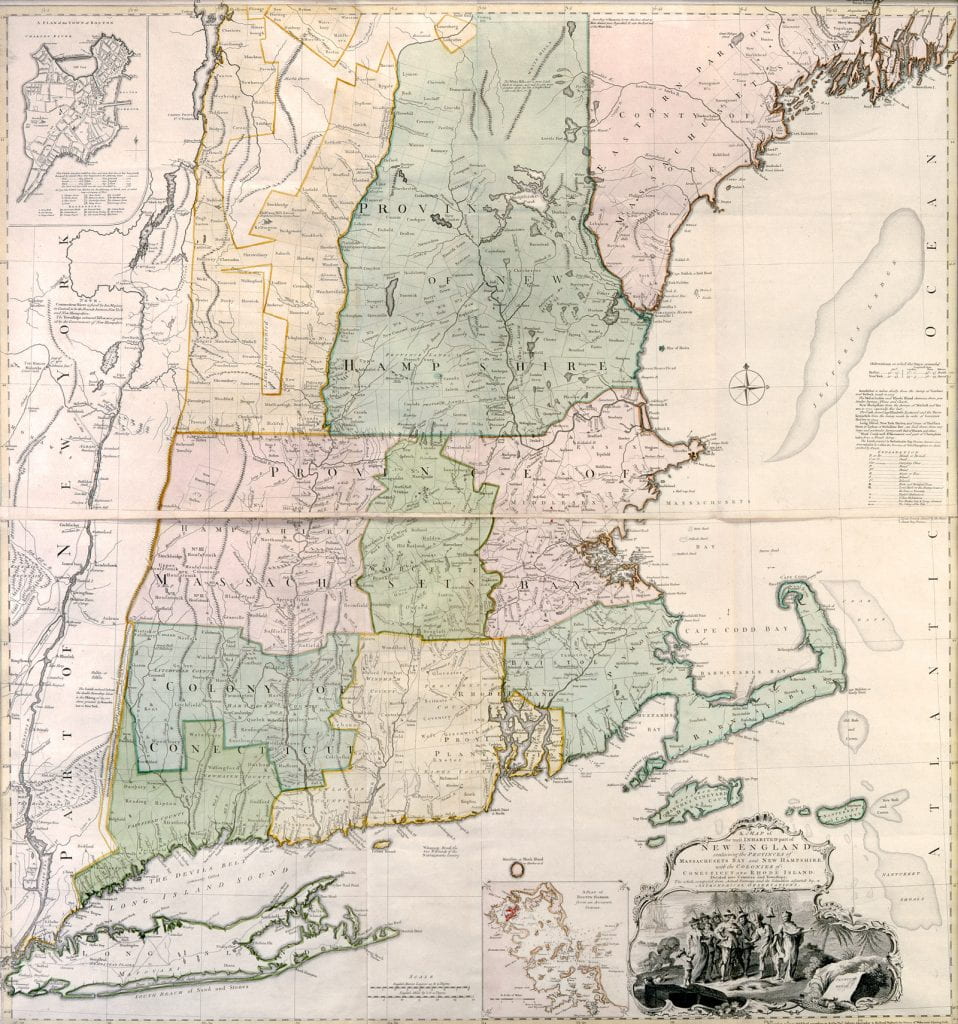

Take, for instance, this map:

This is a map of the New England colonies made about 1753 by cartographer John Green, then copied and imprinted by Thomas Jefferys in London in 1755. How might we come to approach this map in new ways?

What stories might this map be telling? What claims might this map be making?

For me, because of my family background, the stories I grew up with about the Indigenous history of my hometown, and my scholarly training, this map gets me thinking about the relationship between mapping and settler colonialism. Scholars understand settler colonialism to be a particular form of colonialism where newcomers settle and stay on the land, rather than only extract resources and bring them back to their home country. Settler approaches to colonizing then include a process of turning the land that is new, to them, into home country. Yet this land was and is already home to Indigenous peoples. Thus, settler colonialism includes struggle to wrest the land from Indigenous peoples both physically and symbolically in order to fashion it into a new home. This “logic of elimination” (4) is endemic to settler colonialism, but manifests in particular ways in particular places. One manifestation of the underlying logic of settler colonialism that is common in New England is an erase-to-replace narrative that we see produced on maps and in histories, literatures, and more.(5)

This map is making settler colonial claims about this land. The map is entitled “A map of the most inhabited part of New England.” The title might lead a viewer to conclude that sections on the edges of the map or where there are no towns labeled are uninhabited. What counts as inhabited and who is included in that count? Furthermore, note that the towns and settlements that are marked are all English. What kind of claim is this making about whose home this is and what counts as a settlement? I also want to draw your attention to Amherst, homeplace of Amherst College. Amherst sits along the Kwinitekw, or Connecticut River, which is within the traditional territory of the Nonotuck people and their neighbors and relations including the Pocumtuck, Nipmuc, Wampanoag, Mohegan, Pequot, Mahican, Sokoki, and Abenaki nations, among others. Notice that there is a series of boxes that appear on the map in the upper river valley that denote English settlements. Yet according to research on this time period and information posted by the Deerfield Area Historical Society with this map, these boxes do not align with any actual settlements at that time. This means that the map is claiming English settlement where there is none, while not marking Indigenous presence. And yet the map is also engraved with claims about its truth and accuracy: “Plan of the British Dominions of New England in North America composed from actual surveys.” Thus rather than offering just a representation of space on paper, the map is making particular kinds of claims to space and telling a particular kind of story.

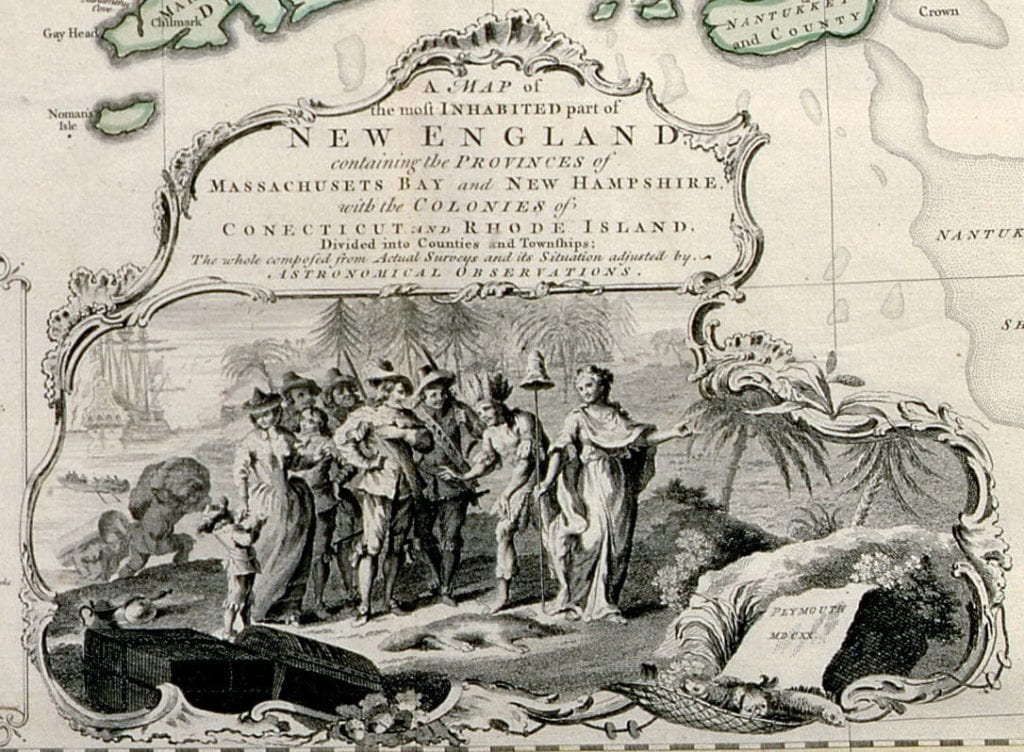

Visual claims made on maps like these invisibilize Indigenous peoples and places. This entire region has been the site of generations of struggle over Indigenous land and ways of life. Yet this map glosses over that story. Take a close look at the image in the bottom right:

What do you see? The map presents an “Indigenous” man submissively welcoming the English newcomers, quieting the long story of diplomacy and resistance, as well as acts of violence against Indigenous peoples. Despite the claims the map might be making, the replacement story was not complete, and much of this territory continued to be contested as Indigenous peoples continued to fight to protect their land. In fact, this map was made just as tensions between Indigenous peoples and the English were heightening. In 1754, this tension would break out into war as many Indigenous people (and their French allies) fought to protect their lands from English expansion into their territories and disruption of their lifeways, in what has come to be known (not unproblematically) as the French and Indian War. In other words this land was, and remains today, Indigenous homeland.

What is not on the map is as important as what is. The upper reaches of the map end before getting to territories that at the time of its making were held mostly by Indigenous peoples who had resisted English incursions for generations. The long history of resistance is precisely why this region is not among the most inhabited, at least not by English settlers. The upper right-hand corner of the map ends at the mouth of the Kennebec River, a river which, if followed upward, leads to Nanrantsouak, known as Norridgewock Village in English, a main village from which resistance against the English had long been launched. This village site is both part of my own homeplace and place of study, and a vitally important place of Indigenous resistance and persistence. It is also a site that has been deeply impacted by settler colonial erasure narratives.

Questions to consider: When you look at the land, what do you see? Have you ever thought about why you see it the way that you do? What might our ingrained expectations and familiar stories be hiding from us? How might we start to see, and relate to, the land and its [story/history] in a different way?

Erasure Close to Home

Where do erasure narratives come from and how can we unravel them?

This powder horn is from the region of the Kennebec River Valley in Maine. It was made by a man from the small town of China, Maine, and belonged to one of the earliest settlers of Vassalboro, Maine, John Gatchel. John served as a guide for Benedict Arnold and his expedition up the Kennebec River to attack the British at Quebec City during the American Revolutionary War in 1775. On the way, the troops spent six days at the site of Nanrantsouak, or Norridgewock village, a vitally important Wabanaki homeplace. Norridgewock Village had been a center of dispute over the Kennebec River Valley for generations prior, as the English tried to claim the land from the Wabanaki peoples, who spent generations successfully protecting it. During their stay at the village site, Arnold wrote in his journal that there remained “some vestiges left of an Indian town.” While his remark was actually an observation of a recently inhabited homeplace, historians and locals have since reinterpreted it to indicate an abandoned ruin. This erasure story has been perpetuated into the present, despite ongoing Indigenous presence and power in the region.

Go Deeper—Listen to Ashley Smith in conversation with Ashlie Sandoval about researching the powderhorn and ways to learn to see through erasure narratives:

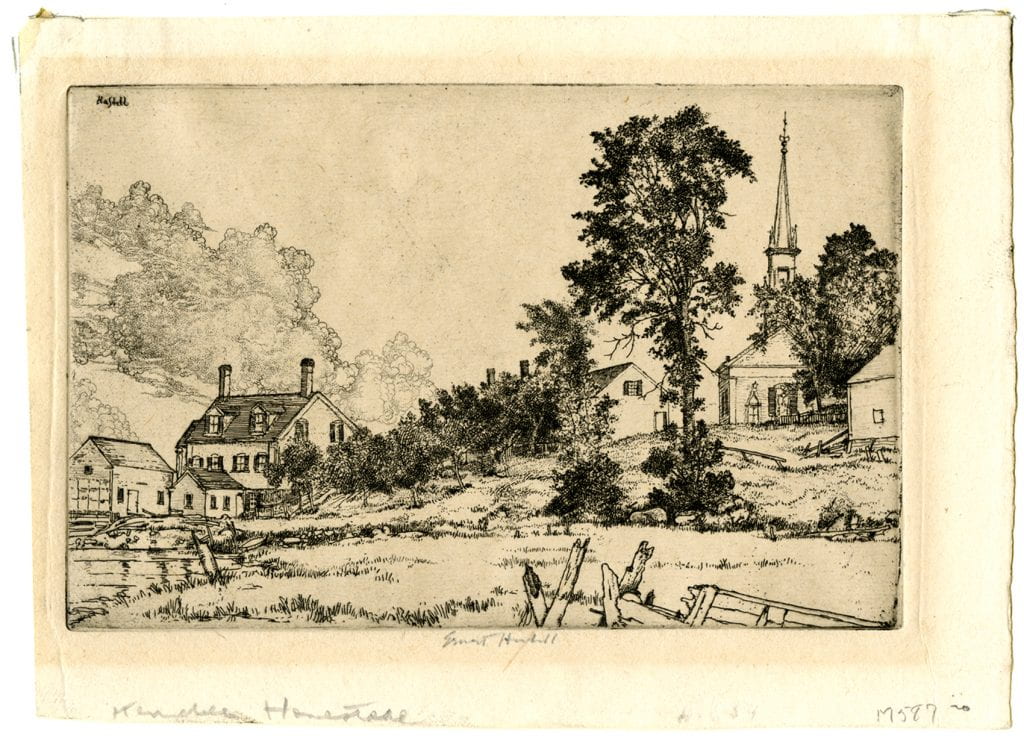

Despite Indigenous continuity, the erasure narrative has enabled many people to believe that this land is no longer Indigenous land. It is a story that enables people to normalize non-Indigenous settlement on the land as part of cultural ideals of “progress.” This is how images of Indigenous pasts are replaced, in people’s minds, with images of settlements and homesteads. Today, we often find ourselves feeling nostalgic for those homesteading days, imagining them to be even further in the distant past than they are, a feeling that also further erases Indigenous presence by pushing it deeper and deeper into our imagined past.

Yet this is and remains Indigenous Homeland. How might non-Indigenous settlers enter into good relations with the Indigenous peoples whose homeland they inhabit? As one of the commissioners for the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, gkisedtanamoogk (Mashpee Wampanoag) has asked of the State of Maine, what would it mean to become neighbors rather than occupiers?(6) And what role do we each play in this work?

Watch the video below to hear Cheryl Savageau recite her poem, “Red,” and discuss the stories behind and within the quilt pictured here, Jazz Autumn: Quarter Note Triplets.

Questions to consider: What happens when viewers see Indigenous presence first? If this approach is new to you, how might looking in this new way prompt you to ask new questions of history and home?

Notes

- Cheryl Savageau, “Trees,” Dirt Road Home, (Willimantic, CT: Curbstone Books, 1995: 17).

- Lisa T. Brooks and Cassandra Brooks, “The Reciprocity Principle and Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Understanding the Significance of Indigenous Protest on the Presumpscot River,” International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 3, no. 2 (2010): 11–28; Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).

- Joseph Nicolar, The Life and Traditions of the Red Man. Edited by Annette Kolodny. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

- Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409; J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “‘A Structure, Not an Event’: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” Lateral 5, no. 1 (2016). http://csalateral.org/issue/5-1/forum-alt-humanities-settler-colonialism-enduring-indigeneity-kauanui/.

- Jean M. O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Indigenous America Series, 2010).

- Adam Mazo and Ben Pender-Cudlip, directors. Dawnland: A Documentary about Cultural Survival and Stolen Children, (Upstander Project, 2018).

You must be logged in to post a comment.