By Samantha Presnal

Recipes are immensely important for home cooks. They inventory the equipment and ingredients, estimating how much we need to feed this many, from a dash of Worcestershire sauce to three pounds of cut-up, skinless chicken. They manage our time in the kitchen, between idle and active, down to the pace: stir a lemon sesame sauce rapidly or add eggs slowly—one at a time. They guide us through the culinary process by speaking to our senses through visual, olfactory, and gustatory cues: heat the paste until it turns a brick-red hue; incorporate rum to taste until the coconut and liquor mixture reaches the right saturation. In a matter of a few pages or a small index card, recipes can tell us a whole lot. Yet the best recipes are often those that leave the most unsaid.

Recipes that stand the test of time contain a secret ingredient—a story. They are stories of people, places, and moments. Rarely spoken out loud or written down, these stories are deeply embedded in between the line-by-line instructions. Recipe stories can reveal hardships endured by families or the hidden labor performed by women. But so often these stories are what inspire us to repeat recipes, as the words, gestures, aromas, and tastes allow us to retell these stories, to relive these memories, to remember our ancestors. And with every repetition, we also shape the narrative. With each addition, omission, or amendment, we leave our mark on the recipe and the story.

This collection renders these stories visible and presents them alongside their corresponding recipes. The featured recipes and recipe stories were contributed by students in a fall 2020 French seminar at Amherst College—Food Fights: Exploring France’s Cultural Tensions through Its Cuisine. Students were asked to select their favorite recipe and tell a story that brings the recipe to life.

As you browse this collection of recipes and listen to the recipe stories, you will discover that recipes are much more than prescription. They are also:

- Ledgers of relationships

- Repositories of memories and emotions

- Artifacts of the imagination

- Records of resilience

- Sources of inspiration and hope

What’s your recipe story?

Share your own recipe story on Instagram using #ACHiddenDrives.

RECIPES

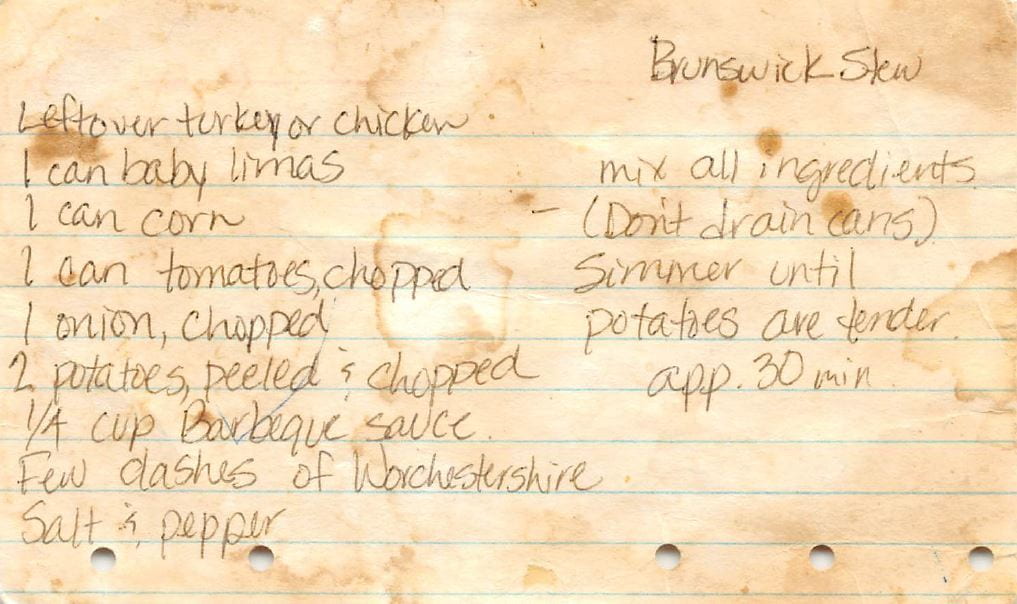

Brunswick Stew

Leftover turkey or chicken

1 can baby lima beans

1 can corn

1 can tomatoes, chopped

1 onion, chopped

2 potatoes, peeled & chopped

1/4 cup barbecue sauce

A few dashes of Worcestershire sauce

salt & pepper

Mix all ingredients (don’t drain cans) and simmer until potatoes are tender. Approximately 30 minutes.

Recipe Story for Brunswick Stew

When I asked my mom about the history behind this dish, she told me that it’s been in the family for at least three generations. Her grandmother used to make this recipe over her fireplace using a swivel arm crane and a cast iron pot. This recipe calls for turkey or chicken, and after Thanksgiving, my great-grandmother would use leftover Thanksgiving turkey to make this dish.

When I was growing up, we would sometimes cook Brunswick Stew over a fire, too—when we camped. We would prepare big batches of it in advance. The campsite we often went to had, attached to the firepit, a section with a cast iron grill that could be lowered or heightened. I remember us shoveling hot coals underneath that grill, and then reheating the stew on top of the grill. Otherwise, though, we ate it in the very different setting of Texas suburbia. We cooked it on the stove in the biggest metal pot that we had (sometimes the simmering bubbles would splash drops of it out on the stove). We always made double batches so there would be plenty of leftovers to reheat later. The dish, like its history, is not very glamorous. But it did fill up hungry bellies.

My siblings and I made some embellishments on this recipe when we were little. We always topped it with grated cheddar cheese, for example. I liked to add the cheese only after the soup had cooled down, because I hated it when the cheese would melt, becoming stringy and messy. It’s a personal preference thing. We also always used to have Brunswick with a side of cast-iron-baked corn bread. (One of those cast iron pans, I found out this summer as I restored the two of them, is decades old!) We’d eat the corn bread with butter and honey. At some point, we started adding slices of corn bread into the Brunswick Stew itself to thicken it and help it cool faster. At some point after that, we would also add the butter and honey accoutrements into the stew itself, too. Probably too much.

Coquito

Pour coconut milk, evaporated milk, condensed milk, and vanilla extract into a blender.

Blend until fully mixed.

Add Puerto Rican rum slowly, tasting to reach right saturation.

Serve in small cups or glasses, and in bottles as gifts.

Recipe Story for Coquito

I have made coquito on two occasions. My mother has been asking my grandmother for recipes for years, but my grandmother refused to share any for a long time. She has kept most of her recipes secret, but did allow my mother and I to make it with her once. We bought all of the ingredients and brought them to her house. She gave us a worried look any mother would be familiar with, and began. We poured in the coconut milk, evaporated milk, condensed milk, and vanilla extract. My mother moved to pour the rum and my grandmother slapped at her hand, characteristic of my grandmother’s disapproval. My mother gave me a look of exasperation as my grandmother blended the ingredients. My grandmother saw the look, sighed loud enough for us to hear over the blender, and gave me the same exasperated look. When the blending was done, my mother moved to pour the rum, but my grandmother slapped her hand again and took the bottle, pouring it instead. My mother said she could have done that, but my grandmother said that my mother would have poured the wrong amount. When my grandmother had finished pouring, my mother took the bottle and poured a little more while I thought about how stubbornness runs in the family.

My mother had the idea to give the drink as gifts. Coquito has proven popular with her colleagues at work. Many enjoy getting a bottle of sweet alcohol at work, where they can indulge before the holiday break without spouses getting upset over abundant and caloric alcohol consumption. I gave the drink as a gift to my college adviser when I was accepted to my first choice college. I also used the drink as a bribe to steal a seat from another college student on an overbooked Peter Pan bus.

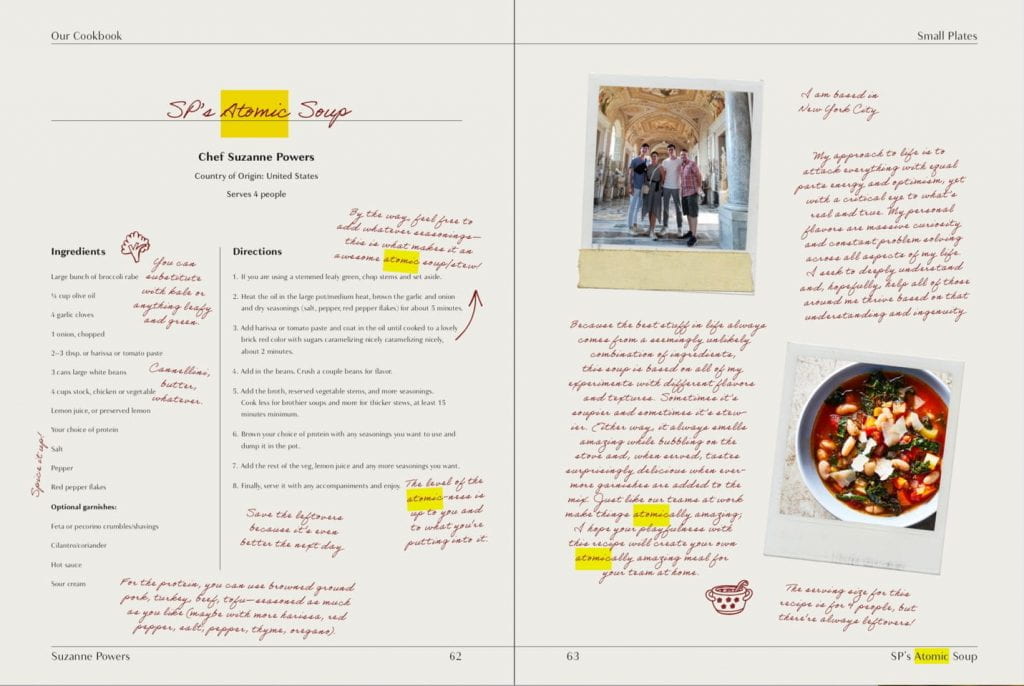

Atomic Soup

Large bunch of broccoli rabe

1/4 cup olive oil

4 garlic cloves

1 onion, chopped

2–3 tbsp harissa or tomato paste

3 cans large white beans

4 cups stock, chicken or vegetable

Lemon juice, or preserved lemon

Your choice of protein

Salt

Pepper

Red pepper flakes

Optional garnishes: Feta or pecorino crumbles/shavings

Cilantro/coriander

Hot sauce

Sour cream

Directions

If you are using a stemmed leafy green, chop stems and set aside.

Heat the oil in a large pot over medium heat. Brown the garlic and onion and dry seasonings (salt, pepper, red pepper flakes) for about 5 minutes.

Add harissa or tomato paste and coat in the oil until cooked to a lovely brick red color with sugars, caramelizing nicely, about 2 minutes.

Add in the beans. Crush a couple beans for flavor.

Add the broth, reserved vegetable stems, and more seasonings. Cook less for brothier soups and more for thicker stews, at least 15 minutes.

Brown your choice of protein with any seasonings you want to use and dump it in the pot.

Add the rest of the vegetables, lemon juice, and any more seasonings you want.

Finally, serve it with any accompaniments and enjoy.

Recipe Story for Atomic Soup

The familiar ambulance sirens penetrated the windows of our New York City apartment every half hour, transporting thousands to the city’s many full hospitals. We were grateful for the comfort of home, yet weeks filled with stress, uncertainty, and an onslaught of terrifying news made it difficult to remember why we should be happy at all. The vestiges of a cold, chaotic winter remained through the end of March as the city fell into a deep, despair-filled darkness. Our only solace was family dinner, when we could leave our work and qualms behind to enjoy a long, lively meal.

After one particularly long day of online meetings, record-breaking numbers on the news, and stressful discussions of our own health, my mom’s cherished Atomic Soup was on the table for dinner. The aromas of Greek feta and perfected broccoli rabe wafted into my bedroom, waking me from my Zoom-induced coma. We sat down for dinner, ravenous and ready for any real conversation that did not have to take place on a computer, staring into the billowing steam from a large chrome pot, filled with some favorite morsels of goodness and nutrition. The warmth of the broth, combined with the heartiness of its ingredients, made an exhausting day immensely better. Over our second and third bowls of the delicious concoction, as my mother would call it, we recounted our days to one another. We filled the air with many thanks to my mother for her beloved creation. For that one hour, we were not consumed by the events that were bringing our city to its knees. We were enjoying a meal that reminded us why we were so glad to be home.

Chicken Soup with Kneidlach (Matzo Balls)

Matzo Balls (Kneidlach)

2 eggs

1 cup water

1 teaspoon oil

1/2 cup matzo meal

Salt

Spices

Thick consistency

Refrigerate

Place in boiling water

Cut with chicken broth

Chicken Soup

Parsley

4 carrots

2 celery

1–2 reg onions

Water to cover {skinned, cut-up chicken (~3 lbs) and veggies}

Boil, remove dirt from top

Low heat

Salt to taste; add {2 tbsp instant chicken sp mix or cube [?] bulliun [sic]

After 30 min. add dill

TOTAL BOILING TIME: 45 min – 1 HOUR.

Serve w/ elbow macaroni.

Recipe Story for Chicken Soup with Kneidlach (Matzo Balls)

Chicken soup with kneidlach (matzo balls) is a cherished dish in my family. We are unsure who originated the recipe, as it has been passed down without any documentation. We do know that my great-grandmother used to make the dish for my grandfather when he was young, prior to her death in the Holocaust. After the war, my grandparents met and moved to Montreal. My grandfather used to make this chicken soup every Sunday afternoon for his family. It was the only time of the week he cooked, because he worked such long hours at the shoe factory. My dad tells me that they usually ate the soup with noodles, but would eat it with kneidlach on special occasions. When my grandfather died, my grandmother took over the recipe, and eventually taught it to my dad. Up until my dad, no one had ever written down the recipe: it was always improvised.

My dad makes the dish fairly often, particularly on certain holidays like Passover. For me, the taste of chicken soup and kneidlach is incredibly sentimental. I associate it with meals at my grandmother’s house and time spent with family. The golden broth is so warm and soothing. It holds all of the flavor from the whole chicken, and is enhanced with carrots, onions, parsley, and celery. Chicken soup is known as “Jewish penicillin” because they say it can cure anything. We eat it whenever anyone has a cold. The kneidlach are the perfect foil to the broth. The chewy “dumplings” gently float through the simmering liquid. The aroma of the soup always fills the entire kitchen and warms up the house. The soup is delicious, and is an important connection to our family history.

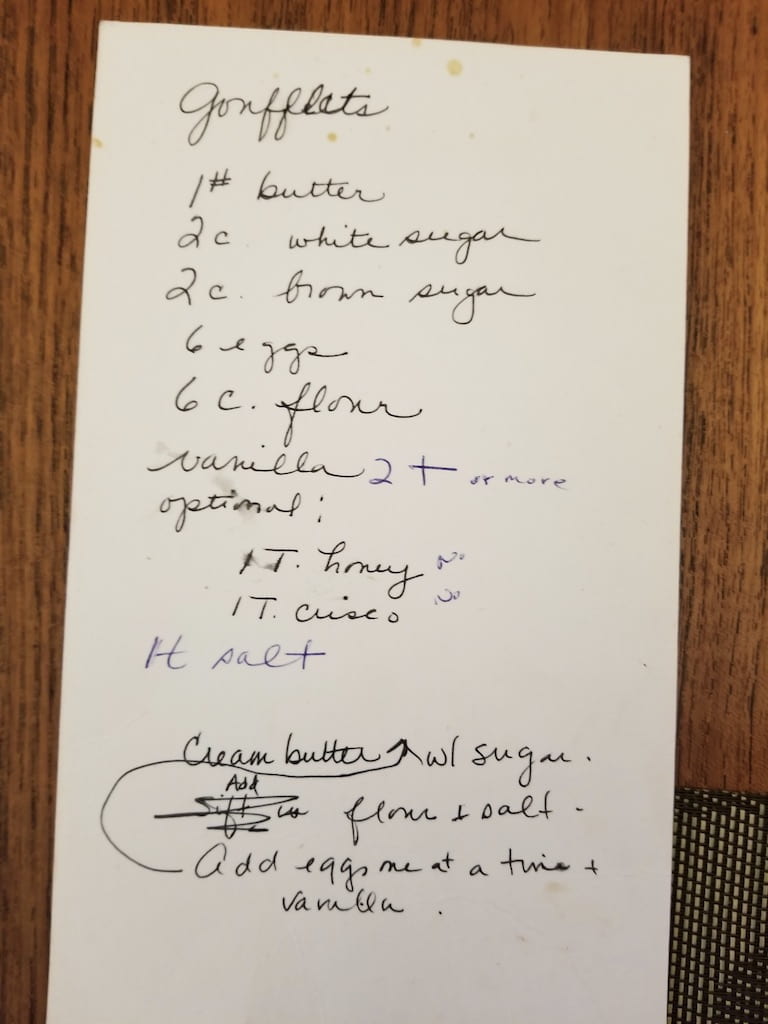

Gauflettes

1 pound butter

2 cups white sugar

2 cups brown sugar

6 eggs

6 cups flour

Vanilla, 2 teaspoons or more

Optional: 1 tablespoon honey

1 tablespoon crisco

1 teaspoon salt

Cream butter. Add eggs one at a time and vanilla with sugar. Add flour and salt.

Recipe Story for Gauflettes

Every year for as long as I can remember, the beginning of December has been the time of Belgian waffle cookies, or gauflettes. A recipe passed down to my grandfather by his grandmother, the cookies have been a staple of my childhood. Though they are delicious, it’s the process of making them that makes gauflettes stand out among the other cookies we always make in December rather than the flavor.

It always seemed to be a chilly day when we arrived at my grandparents’ house to make the cookies. Gusts of wind off the bay rustled the dry leaves around my feet as I scampered eagerly to the door. Walking inside, I was greeted not only by the warmth of the radiators, but was also immersed in the comforting smell of the cookies. The kitchen, full of cousins, aunts, and uncles, created an overwhelming but inviting atmosphere, drawing me in. With everyone assembled, great bowls of dough emerged from the fridge, and the making began. Instead of being cooked in the oven like most cookies, gauflettes are made on the stovetop using large irons. The irons, brought from Belgium by my great-great-grandmother, seemed monstrous: three feet of solid iron that somehow managed to produce my favorite treat. Every year I hoped to be able to lift the heavy iron, yet every year it bested me. The cousins all rotated jobs, most rolling the dough into balls, and two helping my grandfather with the irons. Worn out from wrestling with the heavy irons and the hot stove, my cousins and I would then retreat to a corner and argue about which iron made the best cookies. One iron produced thin crispy cookies, while the other made thicker and chewier ones. We were never able to come to a consensus, but contented ourselves with eating lots of both types.

We still make these cookies every December, only now my cousins and I are able to manage the irons on our own. Every time we go to my grandparents’ house to make the cookies, I still find myself just as excited as I was when I was younger.

Samke Harra

4 lb of fresh red snapper, fillets or whole scaled

17 garlic cloves

1 cup tahini paste

1 tsp hot chili powder

1 cup raw pine nuts

1/3 bunch green Italian parsley, chopped

1 1/2 cups freshly squeezed lemon juice

4 cups water

1–2 tbsp salt (to taste)

5–6 tbsp ground coriander

Olive oil

Rub fish with white vinegar and salt then rinse with cold water in order to tame down any smell.

If using whole scaled fish, cut slits in it.

Rub fish with 1 tablespoon of olive oil and sprinkle some lemon juice on it. If you’re cooking a whole scaled fish, then insert lemon slices inside the fish for flavoring.

Place fish on olive oil–greased cooking tray and bake at 300 degrees F for 20–25 minutes.

In a small pan, mix 1 cup of pine nuts with 1–2 tablespoons of olive oil and cook on medium heat for about 3 minutes or until lightly browned. Be careful as they can burn very fast.

Take half of the pine nuts and grind them with a mortar and pestle and keep the remaining ones for garnishing.

Crush or mince the garlic, then add to a pot with 1 1/2 cups of lemon juice, the tahini paste, water, salt, coriander, and chili pepper.

Heat on stove to medium/high, stirring constantly (very important so they don’t stick or burn). The sauce should have a rather liquid consistency, and should have a nice balance of tahini, garlic, and lemony flavors. If the sauce is too thick, add 1 or 2 cups of water and a bit more lemon juice.

Bring the sauce to a boil while stirring nonstop and then lower heat, add the smashed pine nuts, and keep on cooking and stirring until you reach about 20 minutes of total cooking time for the sauce.

Once the fish is baked, lay it out on a serving platter that is at least 1 inch deep, pour the cooked tahini sauce on top of the fish, and garnish with finely chopped parsley and browned pine nuts.

Recipe Story for Samke Harra

Samke Harra is a dish that originates in Beirut, Lebanon, where my grandparents and my mom and her siblings spent years of their life appreciating the rich and unique flavors of their Lebanese origin. Specifically, this is a dish that hails from Tripoli, Lebanon’s northern port city, but is loved by everyone in the country and beyond. It is considered a show-stopping dish, but for my grandma, it’s just another part of her usual Friday night Shabbat Lebanese feasts. Since leaving Beirut and moving to Paris fifty years ago, my grandma represents the true Lebanese cuisine and brings her passion and love of cuisine into every meal. Samke harra has become a family favorite and a dish that everyone enjoys, meat eaters, vegetarians etc. It incorporates a beautiful, high-quality fish, already drawing you in to its amazing flavor, but surrounded by tahini, herbs, spices, pine nuts, lemon, and the flavors and textures of Lebanon that we all hold so dear. We get that perfect kick of spice with every bite that transports the whole table to that port city. The typical Lebanese seasonings transform a simple fish into a perfectly spicy and memorable family experience.

Although it’s a Lebanese dish through and through, Samke harra can be done in many different ways and can include an array of spices and ingredients that can fit any family’s preferences. This dish is truly the perfect balance of spice, acidity, and a soft calming feeling from the tahini and fish. It has been my favorite dish since I can remember. It’s amazing what a certain dish can do to make everyone feel safe and at home and remind us how important family is and to always remember where we came from.

You must be logged in to post a comment.