Korean Immigrants in Hawai‘i and the Continental United States in the Early Twentieth Century

By Lili M. Kim

Having an atheist father and a Buddhist mother who later converted to Christianity meant that we did not attend any church growing up, let alone a Korean one. (I had a brief fling with being a Jehovah’s Witness in middle school, but that is a separate story.) Growing up in a suburb of Minneapolis, I knew there were many Korean families living in the Twin Cities, and that the best way to be part of the Korean community was to attend one of the many Korean churches. Instead, the only Korean people we socialized with were my aunts, uncles, and cousins. They attended one of the Korean churches, which is how I knew these churches existed. There were three other Korean Americans in my grade at my high school. They were Korean adoptees, with white parents and Anglo-American last names. As much as I tried to be their friend, I was the nerdy kid in honors classes, and they were the popular kids who snuck out to smoke during breaks between classes. In short, they were way too cool for me and infinitely out of my social league, and needless to say, we did not hang out.

Koreans who migrated to Hawai‘i as sugar plantation laborers in the first major wave of Korean immigration to Hawai‘i in 1903 were mostly Christians. The Sugar Planters Association enlisted the help of missionaries in Korea, who tended to settle in urban port cities. The missionaries recruited their converts to migrate to Hawai‘i, in part touting the opportunity to worship freely. Once in Hawai‘i, Koreans began building churches at a furious pace.

The churches served not only as a place of worship but also, perhaps more importantly for these lonely Koreans, as a social hub. This is where they heard news from home, ate Korean meals together, and enjoyed one another’s company away from their backbreaking labor as sugar plantation workers.

But after the Japanese colonization of Korea in 1910, the churches also became a site for anticolonial activism. Koreans gathered to organize, plan, be informed, and argue. Most importantly, they gathered to give what they could out of their meager earnings to financially support the Korean anticolonial activities in Hawai‘i and the continental United States. Which Korean church one attended signaled which Korean leader one supported. While there were official organizations for the Korean anticolonial movement, the churches became very much entangled in the politics of the community.

This photo at the start of this essay shows the congregation of Korean Presbyterian Church in Dinuba, California, in the early 1940s. Dinuba is a farming community in central California, near Fresno. The formation of a small Korean community in Dinuba began in 1909. Fewer than three hundred Korean migrant farmers found a way to make a living, working in vineyards, picking fruits, and growing vegetables. They often worked as tenant farmers in a “10 percent deal.” The landowner would provide them with equipment and pay for all costs involved, and Koreans provided the labor and received 10 percent of the crop or revenue. This was grueling work and they did not make much money. Food was scarce sometimes, and they worked in the punishing sun and hot weather during summer harvests.

And yet when I see this picture, I am amazed because I see nothing of the pain, the backbreaking work, or the relentless stress of survival. Built in 1912, the Korean Presbyterian Church was the hub of Korean community life. Dressed in their Sunday best (beautiful, traditional Hanbok for women, no less), this is the space where they could be someone—a community member, mother, father, spouse, fellow patriot wishing for a decolonized Korea—and not be defined by their physically grueling, low-wage job of picking fruits, farming someone else’s land.

The Sunday ritual of gathering was about more than just worship. It was one aspect of their lives that gave them a sense of dignity, respect, and purpose, as well as a much-needed sense of belonging.

Lili Kim in conversation with David K. Yoo, a historian and vice provost at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has written extensively about religion in Korean American history. Listen here as Kim and Yoo discuss a range of topics: how Korean churches became a social hub for Korean Americans in the early twentieth century; how interconnected religion and politics were in Korean American anticolonial movement in Hawai‘i and the continental United States; and how like all good “families,” the congregation members formed a strong connection with one another against the backdrop of their transnational fight against Japanese colonialism, even as they navigated difficult and complicated conflicts as a community.

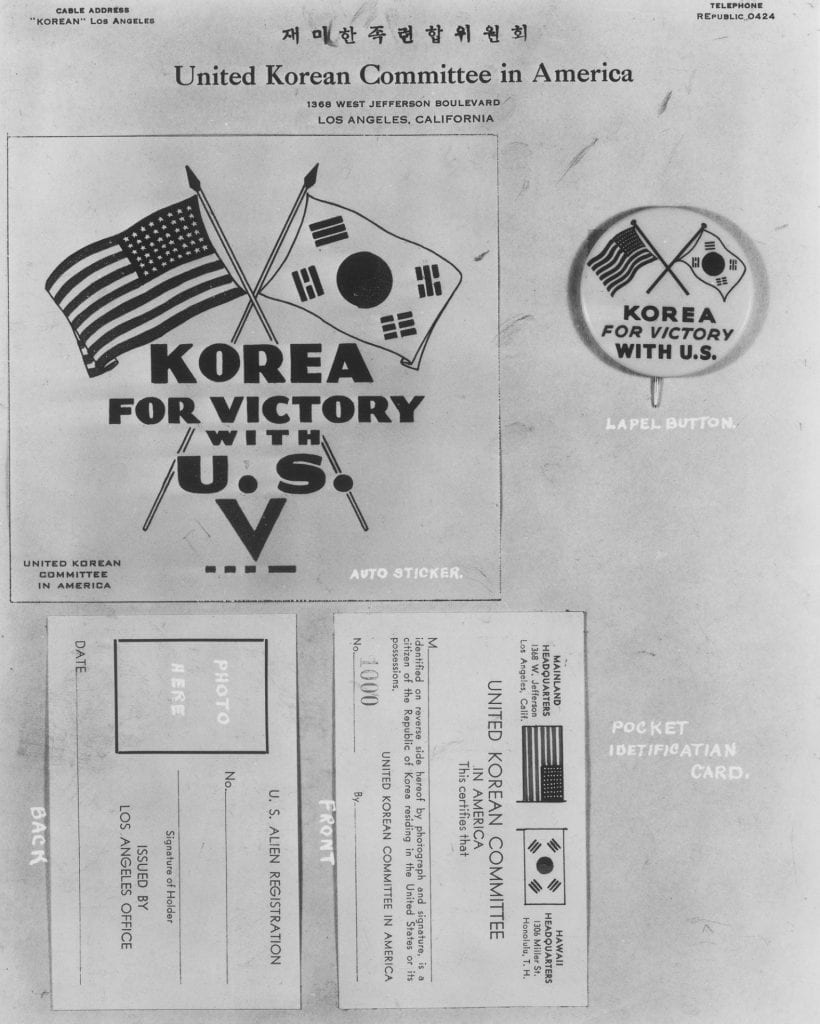

Korea for Victory with the United States

Home was a precarious and confusing place for Koreans in Hawai‘i and the continental United States during World War II. When the United States declared war on Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, Koreans were legally considered “enemy aliens” along with the Japanese on the homefront. The irony of Koreans being accused of having loyalty to their colonizers and being lumped together with Japanese immigrants in the eyes of U.S. officials and the public kicked the diasporic decolonization movement already in progress into high gear.

One of the strategies that Korean American communities used was to demonstrate their loyalty and allegiance to the United States and to argue for the shared goal of defeating the Japanese enemy. The United Korean Committee (UKC) in America was created as an umbrella organization to oversee all of the anticolonial organizations and activities in Hawai‘i and the continental United States, and also to present a united front to the U.S. Intelligence Community, who was closely monitoring Korean American communities for suspicious activity. The lapel button that read “Korea for Victory with U.S.” was issued by the UKC for Korean Americans to wear to publicly declare their allegiance to the United States. Perhaps the more important and immediate reason for Koreans to wear the button was to clearly self-identify as Koreans and not Japanese to evade any unwanted racial violence directed at them for being mistaken as Japanese Americans during the time of volatile displays of hate against “the enemy” on the homefront.

When President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, the fate of Japanese Americans changed forever. Allowed to bring only what they could carry, 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast, two-thirds of whom were citizens, were incarcerated in ten War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps. Euphemistically labeling them “relocation centers,” governmental propaganda perpetuated the image that these internment camps were like summer camps, equipped with all the comforts of the home, and that the evacuation was for the protection of Japanese Americans against public hostility on the West Coast. At the same time, authorities officially justified the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans as a “military necessity.” Japanese Americans had become refugees in their own country.

The tragic history of Japanese American internment and the violation of Japanese Americans’ constitutional rights have since been publicly acknowledged by the U.S. government. An estimated 79,000 survivors of internment won bittersweet redress with the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, granting them compensation of $20,000 each, accompanied by an official apology from the U.S. government: “We can never fully right the wrongs of the past, but we can take a clear stand for Justice and recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II.” (1)

Although no monetary compensation would be enough to make up for the inhumanity and injustices Japanese Americans suffered during their incarceration, the redress movement played a crucial role in helping Japanese Americans come to terms with their painful memories of the internment years. After nearly forty years of trying to forget what happened, Japanese Americans became politicized and empowered by “breaking the silence,” initially by talking about their experience among fellow survivors, and subsequently by testifying in front of the entire nation during the 1981 congressional hearings. By obtaining landmark redress legislation, Japanese Americans finally achieved the goal of receiving a national apology for the injustices they suffered as citizens.

American Flags and Precarious National Belonging

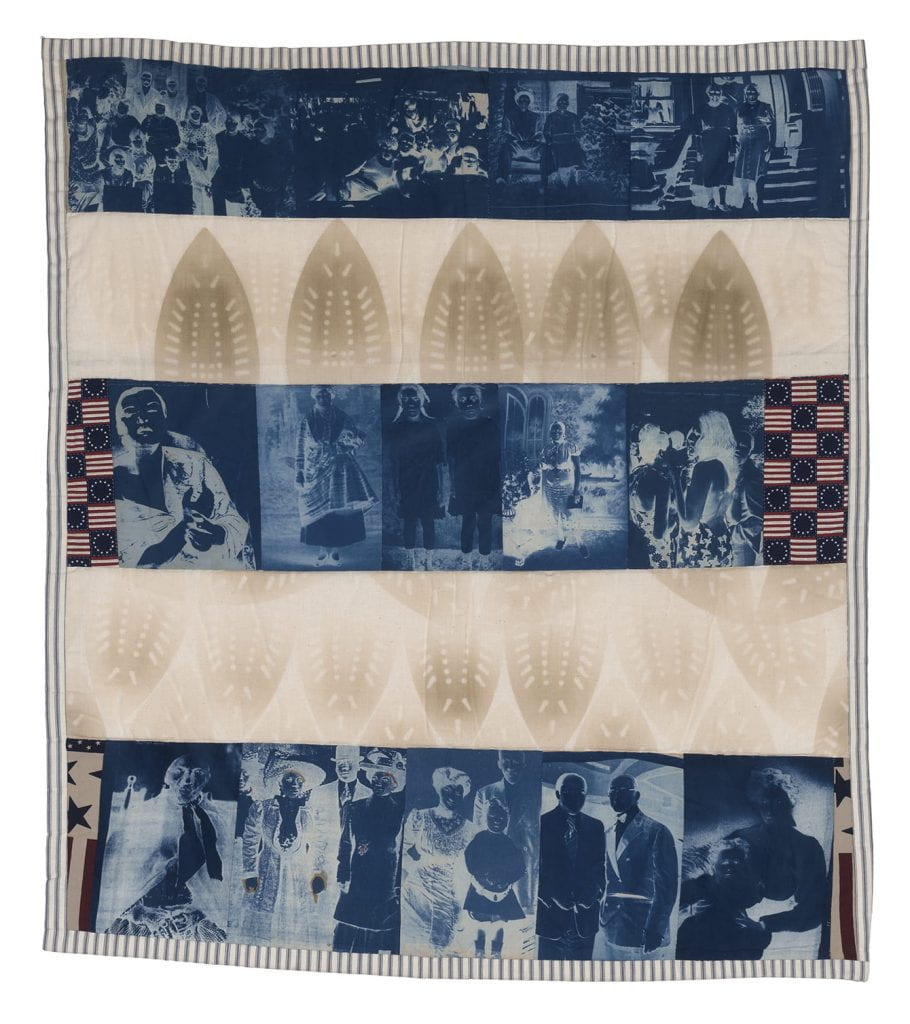

This quilt flag that captures the precarious national belonging of African Americans reminds me of the shared struggles of Korean Americans on the homefront during World War II that I study. After the declaration of war by the United States following the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, Korean immigrants in Hawai‘i and the continental United States were classified as “enemy aliens” along with Japanese immigrants. Because Japan had officially annexed Korea in 1910, Korea did not exist as an independent nation. This was indeed an ironic predicament that Koreans found themselves in: here were Koreans who despised the Japanese for colonizing their mother country, and they were now accused of having loyalty to Japan as colonized subjects of Japan.

The use of American flags by Korean Americans to prove their loyalty and allegiance to the United States as migrants of color, Japanese colonial subjects, and “enemy aliens” brings into sharp relief the falsehood of “the nation of immigrants” myth of the United States. The “nation” never encompassed immigrants of color. Asians were racially deemed unworthy of becoming naturalized U.S. citizens until the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952. The artist Amalia Amaki’s skillful composition of Three Cheers for the Red, White and Blue #15 represents the contradiction of American dreams and identity denied to African Americans. It also reminds us of the futility of embracing whiteness or assimilation as an attempt to belong in the United States for immigrants of color.

The impressive and ironic heroics of the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe during World War II stand as the best examples of children of immigrants of color proving their and their parents’ loyalty with blood. Made up of approximately 23,000 American-born Japanese men, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team is the most decorated unit in the history of the U.S. military. Collectively, they earned more than 18,000 individual decorations, 3,600 Purple Hearts, 350 Silver Stars, and 47 Distinguished Service Crosses.

Unbeknownst to many people even now, there was one second-generation Korean American man, Colonel Young Oak Kim, who served in the 442nd as the only non-Japanese American. This was not a case of mistaken identity; he was assigned to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He was told that there was an all-Japanese unit being formed and that as a Korean he would join them. When he was told this, Colonel Kim boldly responded, “No, you are mistaken. They are Americans, and I’m an American. We are all going to fight for America.” (2)

Born in 1919 as the eldest son to a Korean picture bride mother and a Korean immigrant father, Colonel Kim entered the military by conscription. He was among the first class to be drafted. He had tried to enlist before, but, in his own words, “the military did not want Asians.” Kim trained at Fort Ord in Monterey, California. When he finished the training, ranking as one of the top three in his class, he told his sergeant that he wanted to be a combat soldier. The sergeant advised him to consider becoming a cook, a clerk, or a mechanic in the army because he had the “wrong color skin, wrong shaped eyes to be a soldier.” (3) So he reluctantly resigned to training as an army mechanic until his company commander decided to send him to an infantry officer candidate school. Commissioned a second lieutenant in the infantry upon graduation, he was assigned to the 100th Infantry Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team. With all eyes on this all-Japanese company, he proved himself an intelligent soldier, especially gifted in map reading and planning strategic routes.

Being the only non-Japanese American, Colonel Young Oak Kim was often asked by Japanese Americans why he was in the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. Colonel Kim recalled that there was an implicit understanding that Japanese Americans had to prove their loyalty in this way given that they and their parents and their grandparents had been incarcerated. Colonel Kim made that burden of proving loyalty his own as a Korean American who identified with the struggles of young Japanese Americans: “My position always was that if we among ourselves can’t tell a Japanese from a Korean or a Chinese or any other Asian groups, then the Caucasians definitely can’t. And if you succeed in what you are trying to do, I’m with you, and then we are making a breakthrough for all Asians. You are doing it for Japanese Americans, but you will end up doing it for all Asians.”(4)

The American flag was a powerful symbol and tool for Korean immigrants to claim the United States as their home and ally, with the common goal of defeating the Japanese empire. Korean immigrants on the homefront flew American flags at their churches and fundraiser parades to denote their loyalty to the United States, the country that denied them the right to become naturalized citizens. American-born Korean Americans enlisted in the army to fight for the United States. Korean community members volunteered to work for the Red Cross and bought war bonds to support the war. As investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones tells us, her father always flew an American flag because “he knew that our people’s contributions to building the richest and most powerful nation in the world were indelible, that the United States simply would not exist without us.” (5)

Korean immigrants, too, flew American flags to let people know they were an integral part of the war efforts. Asian Americans still struggle to be seen as Americans and not as the perpetual foreigners that they are depicted as in popular culture and the American imagination. The invocation of the American flag is the ultimate claim to national belonging. Yet African Americans, Asian Americans, and other people of color have limited access to that claim and thus have a thorny relationship to the flag. This uneasy, paradoxical relationship to, and uses of, the American flag is expressed beautifully in Amaki’s quilt flag.

Notes

- Quoted in Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), 378–79.

- Colonel Young Oak Kim, interviewed in Arirang, Part I: The Korean American Journey (Written, produced, and directed by Tom Coffman, 2003).

- Oral history interview with Colonel Young Oak Kim, Korean American Museum Oral History Series, University of Southern California Digital Archives, Korean Heritage Library Collection, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

- Oral history interview with Colonel Young Oak Kim, Korean American Museum Oral History Series, University of Southern California Digital Archives, Korean Heritage Library Collection, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

- Nicole Hannah-Jones, “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True,” NYTimes, 14 August 2019.

You must be logged in to post a comment.